Photographer: Danielle Roper

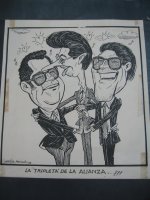

Photographer: Danielle RoperAbove are photos of Miguel Angel Montoya & Bey Avendano as well as Montoya's first cartoon in El Cronista

A political cartoonist is different from other cartoonists who draw for kids, for tv or comic books because the political cartoonist must capture and critique social reality in one image. Hence, a cartoon is often a million words spoken through an image. During my time in Honduras I met with four cartoonists, one of whom is Miguel Angel Montoya. Miguel Angel Montoya is one of Honduras’ first and greatest cartoonists. He started out in the 30s and published cartoons in El Cronista under a fake name when the Military was in control of the country. He was recently recognized and awarded a prize in 2002 for all his work and contribution not only to the art of political humor but also for his revolutionary and radical criticisms of the authoritarian regimes in the mid 20th century. After my conversation with him and two other cartoonists: Bey Avendaño and Napoleon Han, I have come to the following conclusions about the function of political cartoons:

Firstly, political cartoons are the most common and widespread form of political humor in Central America. They appear practically everywhere: in grafitti, on the back of cars, in newspapers, in magazines, posters etc. This has been important for each of the cartoonists with whom I spoke about spreading their messages and mobilizing people. What is so important about cartoonists as against comedians on tv or radio is the fact that anyone can understand a cartoon: a deaf person, a child, an adult etc. Bey Avendaño told me that the only person he feels he is unable to reach with his cartoon is a blind person but with a little help, he says, he will figure out how to do a cartoon in Braille. Also, for people like Montoya, the use of cartoons was important because he could use them to critique the military regimes in power under the pretext that cartoons are not supposed to be taken seriously. Therefore, the advantages of political cartoons are its accessibility and the protection that the art itself can sometimes provide for the cartoonist.

Secondly, political cartoons function as a means of helping literacy in small towns in Central America. For example, both Miguel Angel Montoya and Bey Avendaño grew up in poor communities where most of the people around them could not read. This explains the limited dialogues in the cartoons in Honduras. Even in Nicaragua, which is a poorer country in Central America, you will probably find more dialogue in the cartoons than you can find in Honduran cartoons. Napoleon Han told me that knowing when to use words in your cartoon, and when not to, is the key to becoming a good cartoonists and the key to getting the poorest of the poor on your side. For instance, when Avendaño and Montoya drew a cartoon, they would use one word and the people who couldn’t read would ask “What does that word mean” and they could associate the image in the cartoon with a word and learn to read at least one word that way. For them, this was a way of helping to make people in poor communities literate. This is important because according to both Avendaño and Montoya, critiquing institutions of power is not enough; cartoonists must find a way to be part of the process of solving the problem.

Thirdly, political cartoons are important ways of recording the history of each country. The images that I saw from Montoya’s work tell you what exactly was happening at the time to how times have changed. He also says, that while some of the presidents during the time of conflict are dead, his cartoons live on and by the very least, if you don’t know the president’s policy at that time, you can still laugh at the "pendejo" (assh*le—please see footnote)

One of the major challenges facing political cartoonists today in Honduras is the fact that they are undervalued and earn very little. However, Avendaño says that this has proven advantageous for him because he is able to stay in touch with the people. So he takes the bus, he doesn’t drive, he lives in a relatively poor neighborhood and people have approached him saying “why don’t you do a cartoon about this or that etc?” and he’ll do it and that very person will feel like his voice was actually heard. Essentially, a political cartoonist cannot be out of touch with the people if he is to speak for them.

Consequently, a political cartoonist has a responsibility to the people which is why people like Montoya and Avendano stand so adamantly against the increasing commercialization of political cartoons in Honduras and Central America. In one of Honduras’ presidential elections in the early 1990s, politicians hired young cartoonists to draw and publish images of them to get the vote of poor people. One presidential candidate continuously used the image of “El Guapo” (The Handsome One) with a strong muscular arm reaching for Juana Catracha the damsel in distress. (see footnote). This helped his campaign and he actually won and served as one of Honduras’ most corrupt presidents of all time. For Avendaño and Montoya, this is the most harsh and obvious misuse of the art of political cartoons. The offer of thousands of dollars to cartoonists from these presidential campaigns is a way of keeping cartoonists quiet about the problems in the country. Avendaño says that there is nothing he can actually do about this problem other than to remain true to the people as “un caricaturista combativo.” (combative cartoonist)

Footnotes

*I have spelt the word Assh*le with an asterick because my mommy and daddy read this blog and it is wrong to swear in front of them…but would you like to buy a vowel?

*Juana Catracha and Juan Catracho are the characters cartoonists use to represent the Honduran people. Catracho is the popular/slang word in Central America for Honduran.

© Danielle Roper

No comments:

Post a Comment